Excerpt from "I Was a Stranger and You Took Me In: Pentecostal Responses to the Refugee Crisis"

Excerpt from my chapter, "Going Mainstream(ing): Pentecostalism and the Gender Dimensions of Displacement"

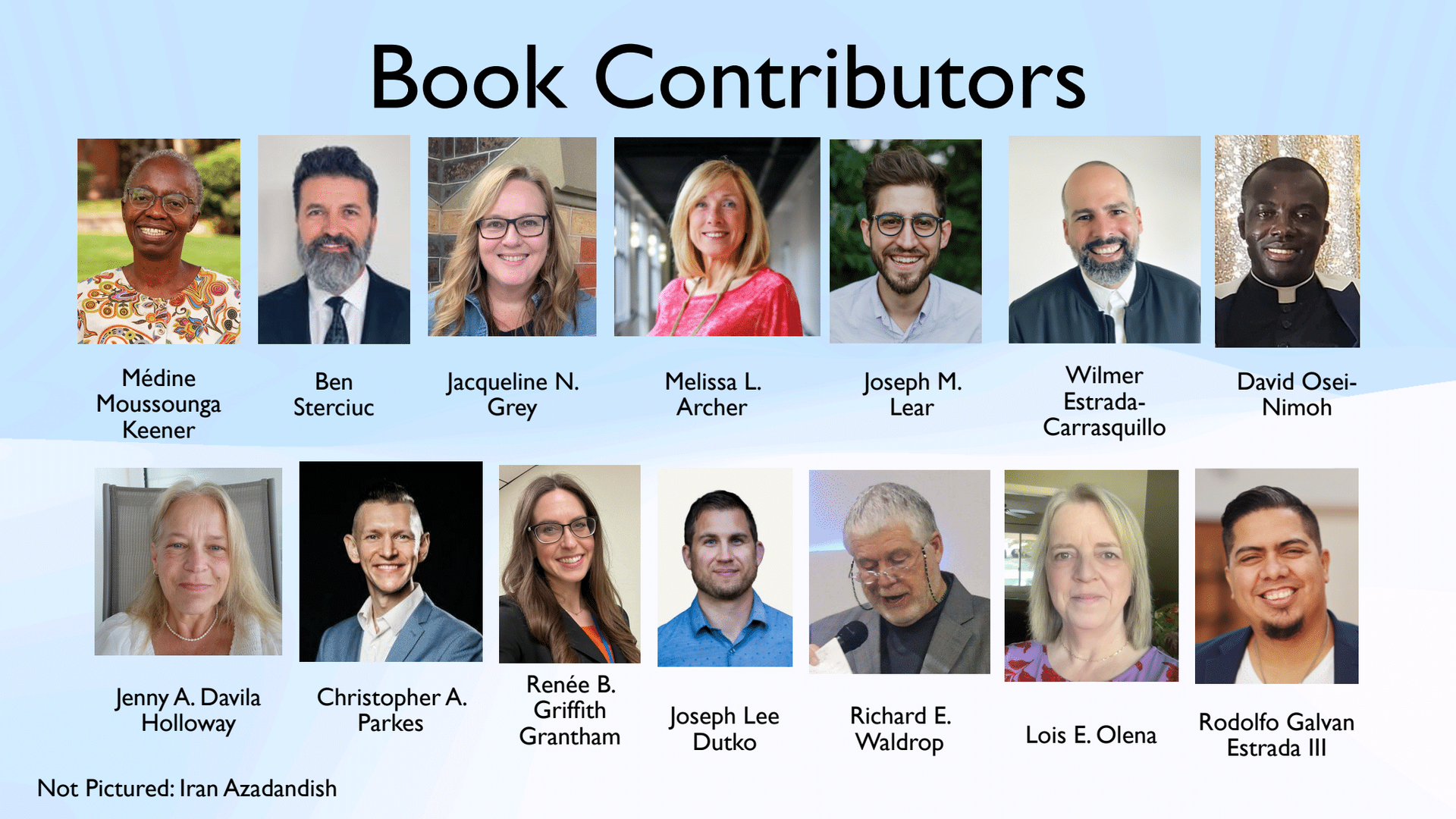

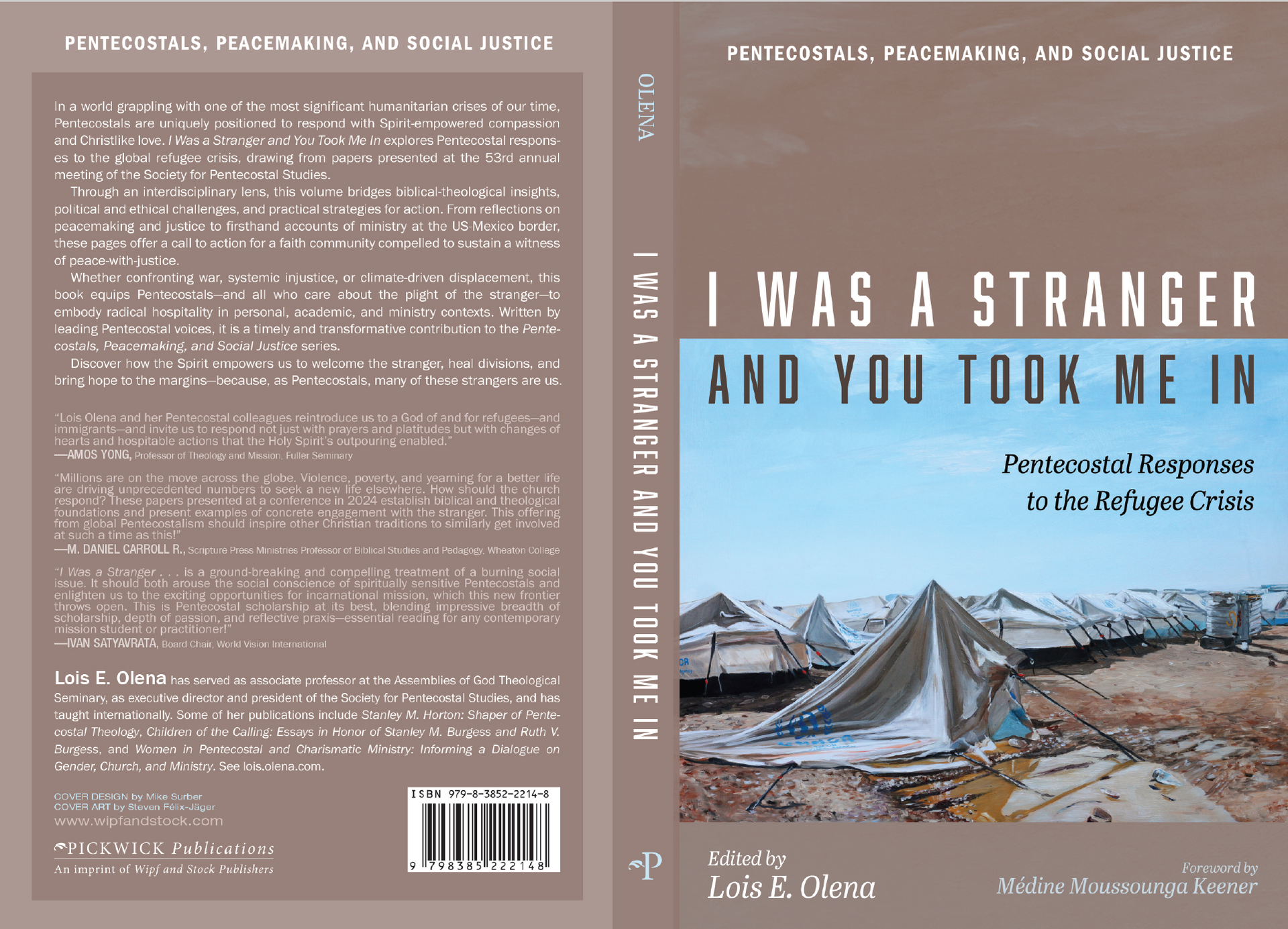

A new book, edited by Lois E. Olena, was recently released as a part of the Pentecostals, Peacemaking, and Social Justice series (Pickwick Publications).

And for the next month only, it's 50% off direct from the publisher!

Simply go to: https://wipfandstock.com/9798385222148/i-was-a-stranger-and-you-took-me-in/ and enter code CONFSHIP at checkout for 50% off!

Additionally, the Kindle version is on sale for just $2.99 ($4.19 CAD) on Amazon until the end of November: https://a.co/d/5jwxCWK

I Was a Stranger and You Took Me In: Pentecostal Responses to the Refugee Crisis contains twelve excellent essays wrestling with what is perhaps the most important humanitarian crisis facing our world, the rise of forcibly displaced persons (or refugees, estimated to be over 115 million people).

If you're a pastor, Christian teacher or leader, work internationally with NGOs or charitable organizations, or are just a concerned Christian, you will find both inspiration and practical help within this work.

The book contains three sections: (1) Biblical-Theological Foundations, (2) Political, Ethical, and Missional Concerns, and (3) Practical Considerations.

My chapter kicks off the third and final section of the book by exploring how the growth and gender dimensions of the refugee crisis intersect with the growth and gender dimensions of Pentecostalism.

I argue that Pentecostalism is a crucial partner in engaging gender mainstreaming (which simply refers to the process of making gender equality a reality) among displaced people because it is uniquely positioned to create faster inroads for making gender equality a reality than the gender mainstreaming policies of other organizations.

In other words, I seek to demonstrate why Pentecostal gender attitudes matter in responding to the refugee crisis and argue that the egalitarian proclivities of Pentecostalism may situate it as a gender mainstreaming partner.

After an introduction, laying out the scope of the problem, and a case study, I offer practical suggestions and action steps for Pentecostal churches and organizations. I close with a personal reflection, included below.

The excerpt below is used with permission from:

Dutko, Joseph Lee. "Going Mainstream(ing): Pentecostalism and the Gender Dimensions of Displacement." In I Was a Stranger and You Took Me In: Pentecostal Responses to the Refugee Crisis, edited by Lois E. Olena, 147-168. Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications, 2025

Personal Reflection and Conclusion

I accepted the invitation to write this chapter because I believe in the subject’s importance. However, I struggled internally during the process of writing. Here I am, writing about forcibly displaced people from my beautiful and mostly affluent island community on the west coast of Canada. Who am I to be writing this to countries I have never been to or organizations in which I have not participated? I propose my pithy point for Pentecostals to “go mainstream(ing)” while displaced women are experiencing tremendous suffering and injustice. Furthermore, I write this knowing there are refugees and displaced people in my own area who need help. Over the relatively short period of writing this chapter, I received a call asking if our church has ideas or space on our property for tiny homes for Ukrainian refugees who are in desperate need of affordable housing. Shortly thereafter, I was contacted by a local politician asking if we could open our church facility as a warming center for “displaced” people in our area during a particularly cold stretch (which we did). On top of that, in an ongoing tragedy, young and often displaced indigenous women in Canada are five times more likely to die from physical violence than non-indigenous women. I had to honestly ask myself, “Am I wasting my time writing this when I could be using that time to help these people more effectively? Would the mental energy expended to write this chapter be better utilized filling out government forms for sponsoring a refugee family?” I don’t know.

But I take solace in this: I wholeheartedly believe that Pentecostal gender attitudes are a matter of life and death due to the intersection of the growth and gender dimensions of global Pentecostalism with the growth and gender dimensions of the refugee crisis. Furthermore, I understand, as this chapter argues, that religious beliefs can often make inroads into enacting change on the ground more quickly than government policy. The gender dimensions of forced displacement and the goal of gender mainstreaming may seem overwhelming or too big to make a difference. But it is important to remember that the first Christians were able to engage and transform a dominant culture that held views about and behaviors toward women that were far more hostile, abusive, and demeaning. And so, if one person’s life is improved (or even saved) because someone reading this recognizes Pentecostalism’s role in gender mainstreaming and acts on it, it might just be worth the effort.

This chapter began with a question: if Pentecostalism is rapidly growing in areas where the population of displaced people are also growing, then what, if any, should Pentecostalism’s response be to the refugee crisis? Recent studies argue that the gender dimensions of forced displacement are a crucial but often-overlooked factor in engaging and responding to the refugee crisis. Similarly, I argue that Pentecostalism and its gender dimensions are an overlooked and rarely mentioned player in the literature on forced displacement. Therefore, the goal of this chapter was to put these overlapping and intersecting factors into conversation with each other by examining the growth and gender dimensions of both global Pentecostalism and of forced displacement.

Government and non-government organizations cannot ignore the influence of Pentecostalism and its ability to make quick inroads to effect change, especially when it comes to gender equality. Similarly, if Pentecostals want to make a larger impact in ministering to refugees, they must be willing to partner with outside organizations in addressing the gender dimensions that cause unjust harm and suffering, and to engage the social dimensions of and collective responsibility to displaced people. In short, I argue that Pentecostalism should become part of the mainstream strategy for gender mainstreaming. Therefore, I call for Pentecostal voices and organizations to participate in gender mainstreaming efforts in places with high populations of displaced people as a way to respond to the Spirit’s call to enact gender equality as a part of a flourishing society. Progressive or regressive gender attitudes among Pentecostals may advantage or disadvantage displaced women. The takeaway challenge for Pentecostals is, will they be ready and willing to go mainstream(ing)?

Order the book at 50% off below by using code CONFSHIP or find the Kindle on Amazon for $2.99!

NEWSLETTER SIGNUP (blog post layout)

ABOUT JOSEPH

Pastor, Author, and sometimes pretends to be a Scholar

Joseph (PhD, University of Birmingham) is the author of The Pentecostal Gender Paradox: Eschatology and the Search for Equality.

Since 2015, he and his wife have together pastored Oceanside Community Church on Vancouver Island, where they live with their four children.