Review of Pentecostal Preacher Woman by Linda Ambrose

"Now more than ever, the stories of Pentecostal women leaders need to be told"

My review of Ambrose's new book on Bernice Gerard was recently published in Pneuma: The Journal of the Society for Pentecostal Studies.

I previously shared about the joint presentation of Ambrose's and my book at a recent conference and the powerful moment it led to, as well as my remarks in that session.

But this is my formal academic review of the book. For those who have access (library, subscription, etc.), the "official" publication of the review is available for download or formal citation HERE on Brill's site.

Review of Pentecostal Preacher Woman: The Faith and Feminism of Bernice Gerard, by Linda Ambrose. Pneuma: The Journal of the Society for Pentecostal Studies 47, no. 2 (2025): 310–13. https://doi.org/10.1163/15700747-04702003

Below is the text of the review reprinted here with permission.

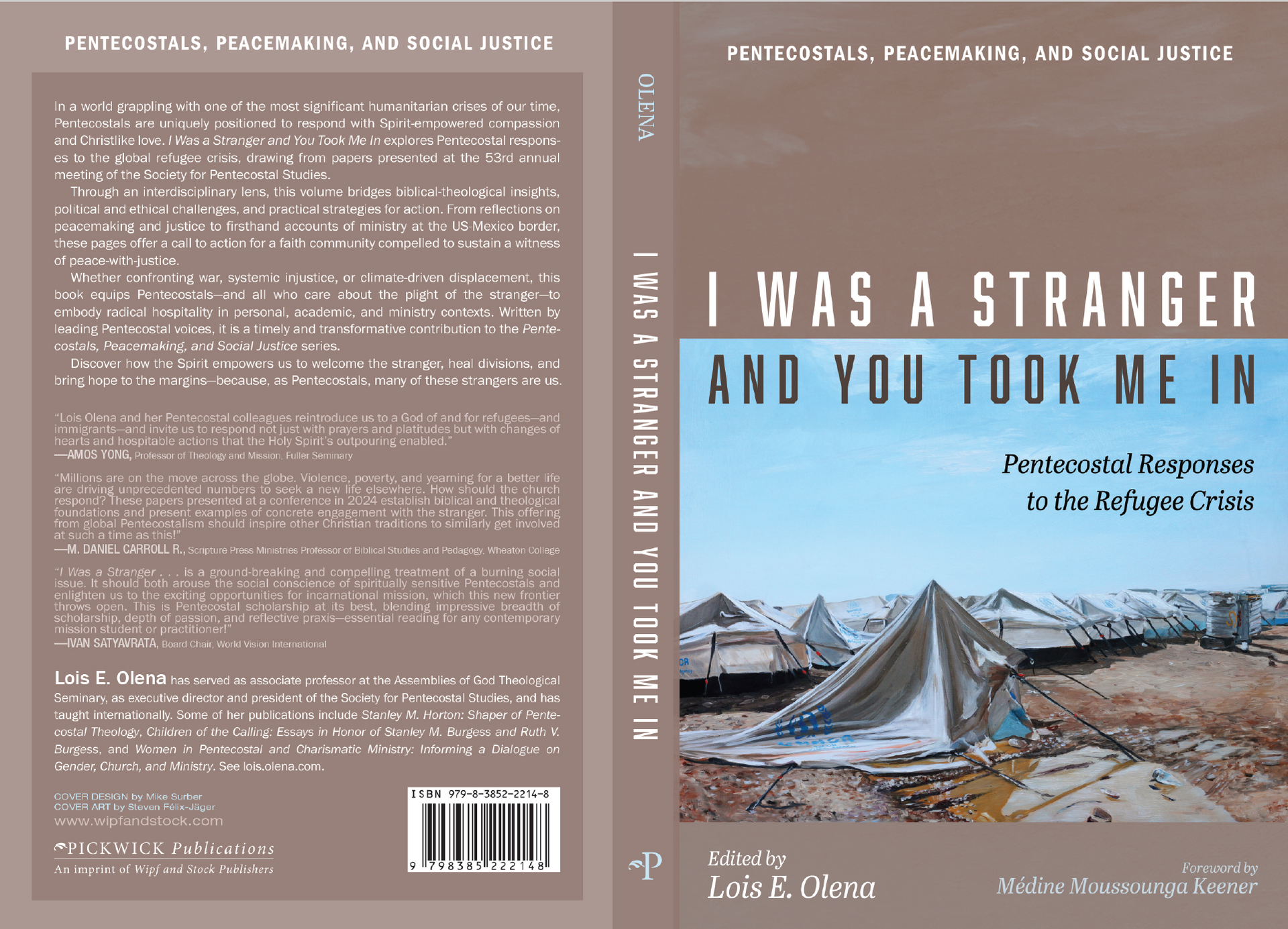

Linda M. Ambrose, Pentecostal Preacher Woman: The Faith and Feminism of Bernice Gerard (Vancouver, BC: UBC Press, 2024). xiv + 303pp. $37.95 paperback ($110 hardback).

Complicated. Complex. Controversial. Messy. Misunderstood. An enigma. Not easily categorized. Beloved. Hated. These are just some of the words used by Linda Ambrose, professor of history at Laurentian University, to describe the life and ministry of Bernice Gerard (1923–2008) in her groundbreaking biography Pentecostal Preacher Woman: The Faith and Feminism of Bernice Gerard. Through her ten years of archival research, conversations with those who knew Gerard, and study of her personal notes and belongings, Ambrose skillfully weaves together history, sociology, and theology to tell Gerard’s story in a way that few but her could do.

The ten chapters tell the story of four parts of Gerard’s life. Chapters 1–3 cover her early years of adoption and a childhood spent navigating the foster care and child welfare systems. This section can hardly be read without tears as Gerard experienced the trauma of physical, sexual, and emotional abuse that would dramatically shape her life as well as lead to her eventual conversion to Pentecostal Christianity. Chapters 4–5 chart Gerard’s remarkable rise from an “unwanted child” (Gerard’s own words) to a successful international writer and traveling evangelist who crisscrossed North America and the globe, attracting crowds who gathered to hear the gifted communicator tell her story.

After some of her travelling companions married and settled into domestic life, Gerard (who never married) shifted her attention to education and chaplaincy work on the campus of the University of British Columbia (UBC), the focus of Chapters 6–7. At a time of rising religious fundamentalism when it was atypical for a Pentecostal leader to embrace a secular education, Gerard defied convention. She dedicated herself to critical reading of scholarly and feminist literature on religion (which is also covered in Chapter 9). Despite retaining her conservative Pentecostal proclivities, Gerard’s willingness to consider other types of thinking paved the way for the wide following of her radio ministry. Chapter 7 is filled with intriguing stories of radio conversations that display Gerard’s “sharp intellect” and “deep mastery of media” (157) in engaging non-Christian callers on the topics of sexuality, Eastern religions, addiction, suicide, and more. The final three chapters ponder Gerard’s pastoral and political life. Chapter 10 describes her “short but colourful career in public life” (202) as a politician on Vancouver City Council and how her Pentecostal spirituality influenced her political engagement.

The first full-length biography of Gerard is a delightful read and a page-turner (I unexpectedly read most of it in one day!). Ambrose’s style is engaging and at times playful, such as when she enters an imaginary conversation with Gerard about footnotes (179). But that is not to say this isn’t the work of a serious historian. It takes a careful and thoughtful scholar to pull off a biography for a life as nuanced as Gerard’s, and Ambrose does it brilliantly. The life of Gerard cannot be oversimplified; there is more to this teetotalling Pentecostal woman with a puritanical appearance than first meets the eye, and Ambrose’s approach represents a masterclass on how to navigate the complexities of popular religious figures. She does not succumb to the temptation toward hagiography—refusing to present an “overly sanitized version of events” (10)—yet addresses the imbalance and “implicit biases and assumptions” in scholarship “that privilege progressive women to the exclusion of others” (13). Using a woman-centred approach, Ambrose allows Gerard’s voice and writings to guide the conversation and conclusions, believing that “women’s religiosity should be respected” and that “religious women should be heard in their own voice” (14).

Gerard considered herself to be a feminist, a label that confused both conservative Pentecostals and liberal politicians who couldn’t reconcile Gerard’s paradoxical relationship between her feminism and traditional religious views. But Ambrose deftly “allows” the socially-progressive feminist Gerard to coexist with the conservative Christian Gerard without explaining either away. Gerard’s social stances and alliances were messy, and Ambrose does not seek a tidy explanation, preferring to allow Gerard’s often-complicated views to evolve over time. Those on either side who would seek to anoint or use Gerard as an exemplary Christian moral crusader or as a model social progressive will be frustrated with Ambrose’s portrayal. Both stances would be an oversimplification of a complex life and legacy. With the progressive political crowd, Gerard is perhaps best known for her colourful and unpopular public protests against abortion, public nudity, and standards of decency in popular entertainment. But on the conservative religious side, Gerard was sometimes equally unpopular for her feminism, ecumenism, social justice work, and compassion toward lesbians and gays. She was also an unlikely forerunner for Pentecostal cooperation with Catholics. Gerard spoke of distinguishing herself from “conservative other-worldly evangelicals” (219) even as she was labeled as such by some outsiders. Gerard was too conservative for society at large and too moderate for dogmatic believers, and Ambrose wisely does not minimize the dissonance.

A potential disappointment for readers—and my main critique—is that for a book titled Pentecostal Preacher Woman, there is very little insight into Bernice’s life as a preacher and pastor. Chapters 8–9 are simultaneously the most interesting but also unsatisfying chapters of the book. In 1964, the Pentecostal Assemblies of Canada (PAOC) invited Bernice and her longtime ministry partner Velma McColl Chapman to become the founding co-pastors of Fraserview Assembly in Vancouver. Despite pastoring the church together for 21 years, Ambrose gives very little detail of Gerard’s pastoral life and calling. Chapter 8 importantly tells the story of how Gerard navigated the patriarchal systems of the PAOC and begrudgingly defended herself (and women’s ordination in general) as a woman leader to her national peers in the 1980s. But the chapter, the shortest of the six that cover her ministry vocations, contains only a few stories from General Conference episodes in the 1980s and left me wondering what her life as a local church pastor was like and how she was received within her congregation. The story of Gerard’s parish ministry life is largely untouched and untold. Although Ambrose did the admirable work of collecting twenty years of Gerard’s sermon notes, there are only occasional references to them and her voice as “Pastor Bernice” is largely absent in the book.

Similarly in Chapter 9, despite the extreme rarity of two women co-leading a church together (or a single woman for that matter)—a ministry model that “defied existing gender constructs” (189)—it is puzzling that Ambrose spends more time pondering the complexity of Gerard’s domestic arrangements with Velma than she does their pastoral life together. Although Ambrose argues that it is “highly unlikely” the PAOC will soon again see two women co-pastoring a church and that “gender was central” to their experience as pastors together (188, 199), we don’t get a lot of explanation or insight into how their pastoral relationship worked (only a brief job-like description of how they divided the responsibilities). The chapter’s stated attempt to explore their ministry model “through a critical gender lens” never fully materializes. Admittedly, this critique likely has a lot to do with my interest and role in pastoral ministry, as well as my academic research on women in pastoral leadership. Many readers likely will not mind or notice these absences. I’m a pastor-theologian and Ambrose is a professor-historian, which likely explains the difference in expectations for these chapters.

Even with this noticeable missing content from Gerard’s pastoral life, the contributions made by this biography far outweigh any shortcomings. Gerard’s life is a fascinating case-study that will appeal to many audiences and contribute to several fields. Scholars and historians (and even everyday participants) of Canadian Pentecostalism, women’s and feminist studies, religion and gender, politics, child welfare systems, and the local history of Vancouver and BC will all benefit from studying Gerard’s life. Additionally, Christian leaders who work as pastors, politicians, teachers, university chaplains, or social workers will all find plenty of material to reflect on in their vocational callings.

Perhaps now more than ever, the stories of Pentecostal women leaders need to be told. Despite being named British Columbia’s most influential spiritual figure of the twentieth century, receiving appointment as the first female chaplain of any faith tradition at UBC, serving as the first PAOC university chaplain—male or female—in Canada, being the first woman to ever officiate a Baccalaureate service at UBC, and acting as a spiritual mentor to the current General Superintendent of the PAOC (David Wells), Gerard remains far from a household name in Pentecostal, PAOC, or other circles. It’s a sad indictment on North American Pentecostalism that Gerard’s story as an influential Pentecostal woman pastor and leader remains an aberration. I can only imagine what Gerard would think that we must still defend women in Pentecostal leadership, a topic she herself said she was “bored” with and had “no time for” (17, 182). Unfortunately, it’s hard to imagine a single woman such as Gerard, or two women together such as Bernice and Velma, pastoring a large and influential PAOC church today as they did then. Hopefully Ambrose’s highly readable yet meticulously researched work will change that. As Ambrose exclaims toward the end of the book, “How I would dearly welcome the chance to chat with Bernice Gerard about all this!” (238).

Joseph Lee Dutko

Independent Scholar, Parksville, BC, Canada

www.josephdutko.com | joseph@oceansidecc.ca

NEWSLETTER SIGNUP (blog post layout)

ABOUT JOSEPH

Pastor, Author, and sometimes pretends to be a Scholar

Joseph (PhD, University of Birmingham) is the author of The Pentecostal Gender Paradox: Eschatology and the Search for Equality.

Since 2015, he and his wife have together pastored Oceanside Community Church on Vancouver Island, where they live with their four children.